In 2016, there was a huge public outcry, based on the assumption that false news strongly influenced the outcome of the US presidential election. Some sources provide information that fake news about the US election was more popular on Facebook than articles from the largest traditional news sources. However, the scope of active use of fake news is not limited to politics.

For example, this news about Canadian, Japanese and Chinese scientists studying the effectiveness of treating leukemia using the root of a common dandelion was passed from user to user more than 1.4 million times in 2016. Fake news is a cause for concern because it can affect the minds of millions of people every day. Such overlays align them with traditional methods of hacking, such as advertising, and the most recent – search engine manipulation (search engine manipulation) and search options (suggested search effect). These have led to the emergence of the term post-truth, which became the word of the year in 2016 by Oxford words (Norman, 2018). Thus, fake news is defined as a piece of news, which is stylistically written as real news but is completely or partially false. It is recommended that members of the media use the terms fake information and misinformation instead of fake news.

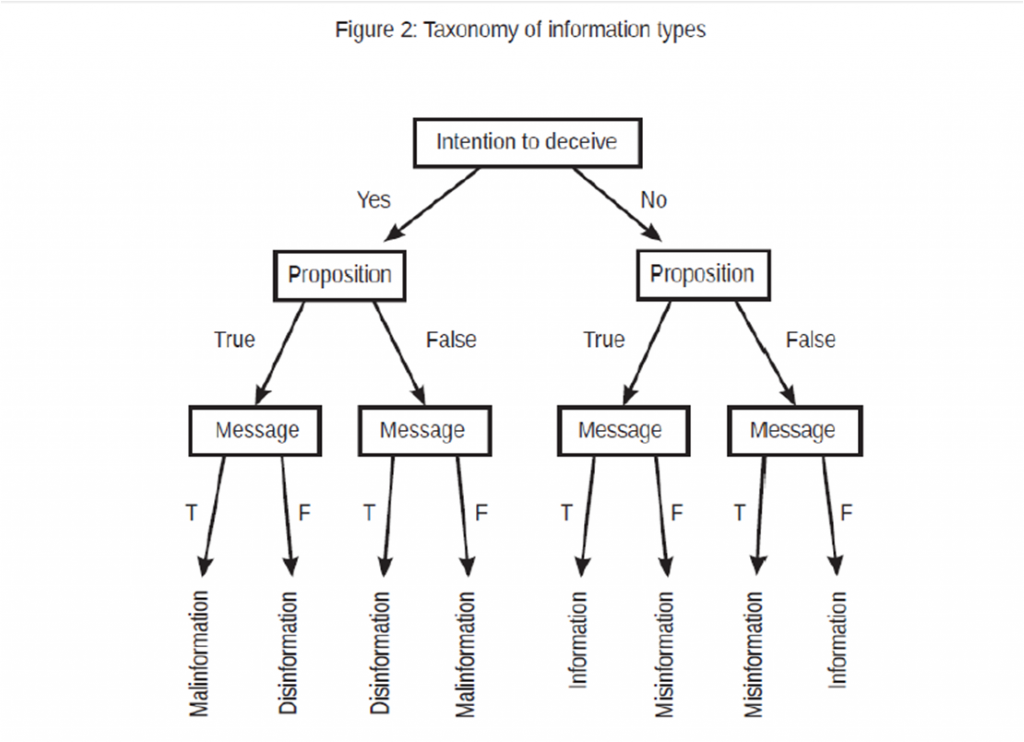

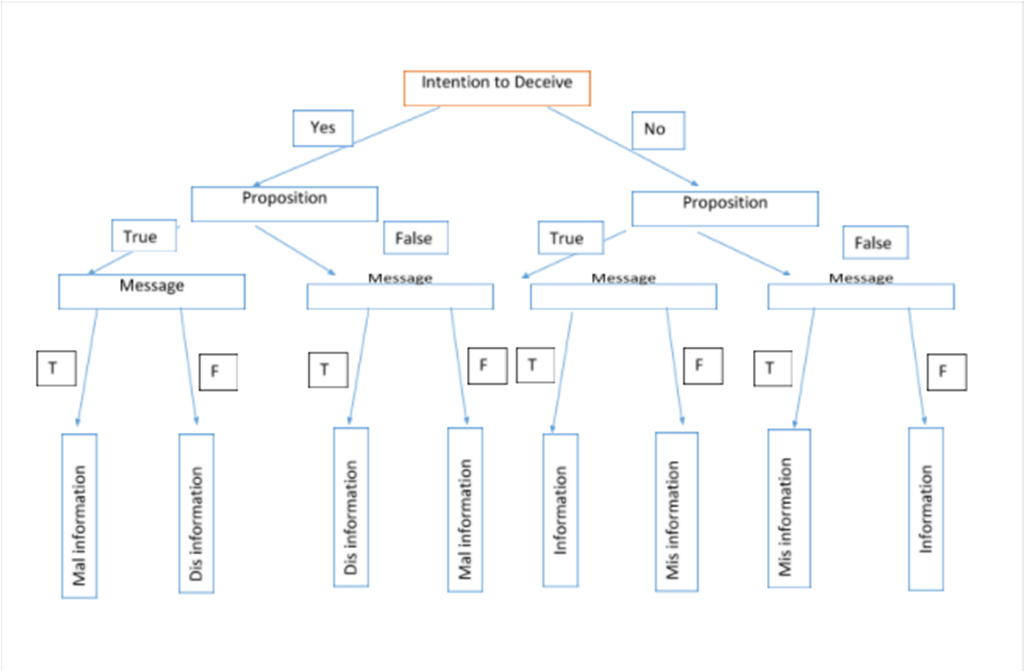

There are different types of this module and they are in the range of “information disorder”. This crisis is much more complicated than what is called “fake news”. Much of the discourse on ‘fake news’ conflates two notions: misinformation and disinformation. It can be helpful, however, to propose that misinformation is information that is false, but the person who is disseminating it believes that it is true. Disinformation is information that is false, and the person who is disseminating it knows it is false. It is a deliberate, intentional lie, and points to people being actively Dis informed by malicious actors. A third category could be termed mal-information; information, that is based on reality, but used to inflict harm on a person, organisation or country. An example is a report that reveals a person’s sexual orientation without public interest justification.

It is important to distinguish messages that are true from those that are false, but also those that are true (and those messages with some truth) but which are created, produced or distributed by “agents” who intend to harm rather than serve the public interest. Such mal-information – like true information that violates a person’s privacy without public interest justification – goes against the standards and ethics of journalism. COVID-19 is an unprecedented global health crisis that will have immeasurable consequences for our economic and social well-being. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a deeply concerning pandemic that is alarming in both its severity and its spread (WHO 2020a). The initial growth of the virus was exacerbated by inaction and an absence of reliable evidence on how best to control the worsening situation. As COVID-19 spread, exaggerated information and a lack of trusted data hampered proper communication, delayed appropriate action and led to suboptimal decision making. The initial production and publication of vast amounts of valid and invalid messages led to an over-consumption of information, which was misleading, unsettling and confusing for a largely uninformed public.

Moreover, there may be an elephant in the room because much of the false information spread so far has not been unreliable health advice but is state-disseminated propaganda designed for destabilising political ends (Sukhankin 2020). For this reason alone, governments, academics, digital platforms, fact checkers, concerned institutions and the public urgently need a shared understanding of what is meant by the terms Mis-, Dis- and Malinformation. Without a scientific understanding of these concepts, there is a danger of significant democratic consequences from this global health crisis. The information systems research community can actively work to help avoid this.

This paper suggests that: (i) analysing all types of information is important in the battle against the COVID-19 Infodemic; (ii) a scientific approach is required so that different methods are not used by different studies; (iii) “misinformation”, as an umbrella term, can be confusing and should be dropped from use; (iv) clear, scientific definitions of information types will be needed going forward; (v) Mal information is an overlooked phenomenon involving reconfigurations of the truth.

This article is part of a series of articles contributed by board members of WCFA.

The views and opinions published here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of the publisher.

Be the first to comment on "Impact of Mis-information, Dis-information & Mal-information on Reputation during the COVID-19"