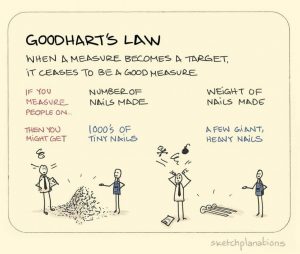

“When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.”

– Goodhart’s law

This cartoon strip illustrates the kind of conundrum in which brand custodians often find themselves. Without a metric, an initiatives can become directionless and cannot be optimised (and more importantly, cannot be measured for their ROI). Yet, with a metric, they become unidirectional and optimised just to that one end of maximising that metric, potentially at the cost of other crucial objectives.

We witness that from primary school classrooms where grade optimisation is prioritised over lateral learning, to government functioning, where GDP calculations are manipulated to quash political insecurities (Read: How Nigeria’s economy grew by 89% overnight). Naturally governments encounter this often. Playing around with metrics which can be considered as measure of their establishment’s performance is a part of the game. A lot can hinge on it – re-elections to a country’s health.

Perhaps the most common example of Goodhart’s law in action takes place in the context the Ease of Doing Business index released by the World Bank each year. These rankings roughly indicate the structural integrity of policy environment of a country and the efficacy of the bureaucracy to enforce it. Its implication can be the levels of FDI/FIIs that the countries can attract, and therefore crucial balancing of their current account deficits. (One could also argue that the generally narcissistic national leaders consider this as one of the items on their report cards).

In his book “The Rise and Fall of Nations”, Ruchir Sharma illustrates a good example of a fracture in this metric:

“In 2012 President Vladimir Putin set a goal of raising Russia’s rank for ‘ease of doing business’ from 120 to top 20 within six years, and he soon saw results. By 2015, Russia was ranked at 51, more than thirty places ahead of China, and sixty places ahead of Brazil and India. That raised a question: If it was so easy to do business in Russia, why wasn’t anyone doing business there? Moscow in 2015 is increasingly hostile to and isolated from international business, far more so than China or Brazil or India.”

That happened because of Moscow’s focus went from truly cutting down red tape and making it fundamentally easy to do business, to “cracking” every parameter of the index at that time.

Closer to home we’ve witnessed Indian political leaders going to such lengths to look good. UPA government’s MGNREGA, passed in 2005, was a benevolent scheme crafted by some of the finest policy minds of India of the last two decades. The goal was to guarantee at least 100 days/year of employment to every rural household that volunteers, else they’re entitled to unemployment benefits. We can guess where that headed. 10 years later it was a colossal disaster – individuals have received benefits and work payments for work that they have not done, or have done only on paper, or are not poor. But the biggest manifestation of the law were found in stories of labour digging holes and refilling them, to clock up the number of beneficiaries, number of hours and the overall degree of success of the scheme. This was UPA’s brand, and its delivery was manipulated to make it look like a success.

If you’re in communications, it’s not hard to imagine how this phenomenon takes shape. Metrics like impressions, views and hits can vaguely describe success, but not actual impact. PR doesn’t have a universally agreed upon set metric either – in absence of which sometimes PR efforts get oriented towards acing a certain metric that may have very little to do with the real goal. Sujit Patil, who heads corporate communications at Godrej Industries, has, on more occasions than one, advocated for Return on Objective instead of Return on Investment as the measure of reputation management efforts. Ruchir Sharma, in extension to the example above, went on to say “To the extent possible, I try to avoid relying on numbers that are vulnerable to political manipulation and marketing”

There is a fascinating concept called the Observer Effect which stems from the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle in quantum mechanics, which says that “Simply observing a situation or phenomenon necessarily changes that phenomenon”. An example of it is that if you’re trying to observe an electron, for it to become detectable, a photon must first interact with it, and this interaction will inevitably change the path of that electron. This also means that the only way to let the electron to do whatever it is meant to do, is to not try and observe it. Maybe this can give us hint as well, on when and what to measure, while retaining the integrity of an initiative.

Can you think of more examples of governments tweaking metrics or how they’re measured? Or a brand initiative that went awry when communicators aimed for the wrong kind of goals? Share with me in comments below or on Twitter @HemantGaule.

Last week on State Craft:

Leave a comment